At my age even I am timid when faced with a scarecrow in the field – Issa

Category: Poetry

-

From “The Uncured World” by Elisabeth Frost

I decide to name my body. Jane. Jean. Janet. I’ve never liked names that begin with that uncertain sound, wobbling between consonant options like a bowling pin on the fritz. But I need to embrace a thing I have never cared for. As a kid I loved the game of telephone, one mishearing after another, the transformation, the delight at the end when the secret of the final whisperer was unveiled. Incense, insect, instant. Drench, trench, wrenched. Language, languish, anguish. We played at the margins of the senses, pretended loss where there was none, made the privilege of hearing into a game. One erasure, another erasure. Janet—unfixed, unmoored, unwell—time to mobilize.

-

Indeterminacy by J. Mae Barzio

How many times I tried to record the Goldberg Variations

Once in Iceland another time in California

It was Mercury in retrograde I didn’t get the chords right

You see I wanted a different kind of music

One that felt like a foreign city or ice cracking

A prediction of snow and then the snow itself endless

I wanted the blue stripes on your shirt the paleness of your underarm

The whiteout of a spring blizzard, everything unexpected

See I didn’t do well with indeterminacy—the blank sides of a dice

The piano chord I recognized but couldn’t name

A different kind of intimacy because I was tired of being unsurprised

Behind me in the photo the black river unraveled

Like a list of the dead children or the ones I never had

The field split open like a lip

I asked the river for answers but heard nothing

The path was obscured by another person’s tracks in the snow

Snow falling so slowly that no one noticed it. -

Ghosts

There are ghosts in the room.

As I sit here alone, from the dark corners there

They come out of the gloom,

And they stand at my side and they lean on my chairThere’s a ghost of a Hope

That lighted my days with a fanciful glow,

In her hand is the rope

That strangled her life out. Hope was slain long ago.But her ghost comes to-night

With its skeleton face and expressionless eyes,

And it stands in the light,

And mocks me, and jeers me with sobs and with sighs.There’s the ghost of a Joy,

A frail, fragile thing, and I prized it too much,

And the hands that destroy

Clasped its close, and it died at the withering touch.There’s the ghost of a Love,

Born with joy, reared with hope, died in pain and unrest,

But he towers above

All the others—this ghost; yet a ghost at the best,I am weary, and fain

Would forget all these dead: but the gibbering host

Make my struggle in vain—

In each shadowy corner there lurketh a ghost -

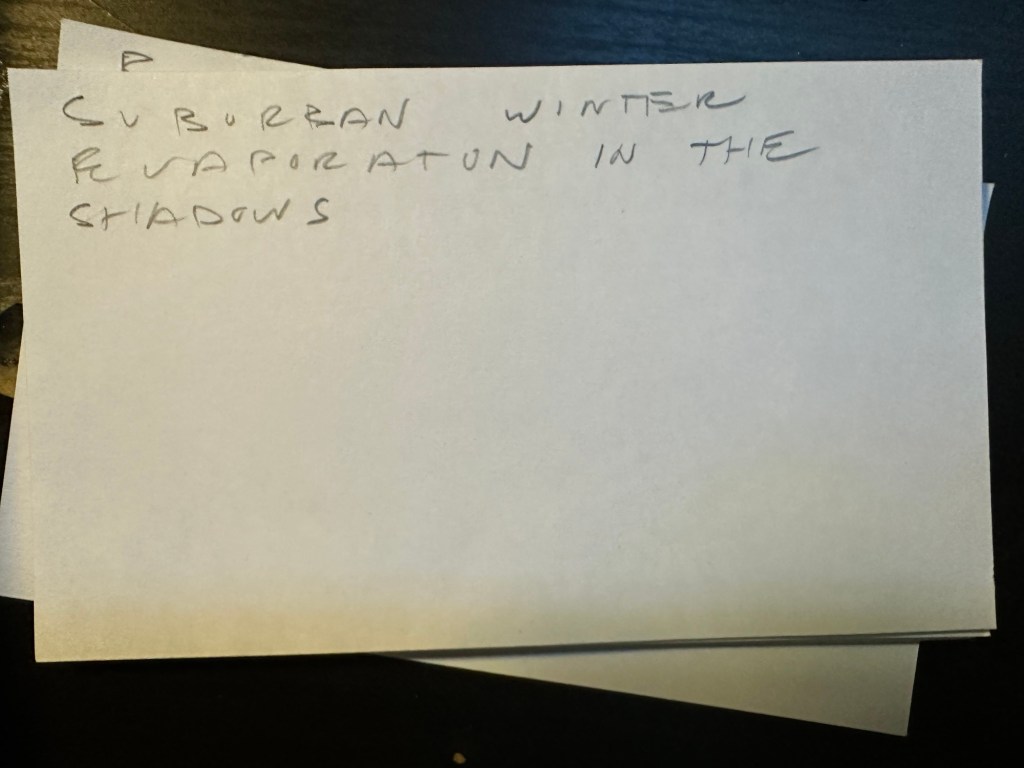

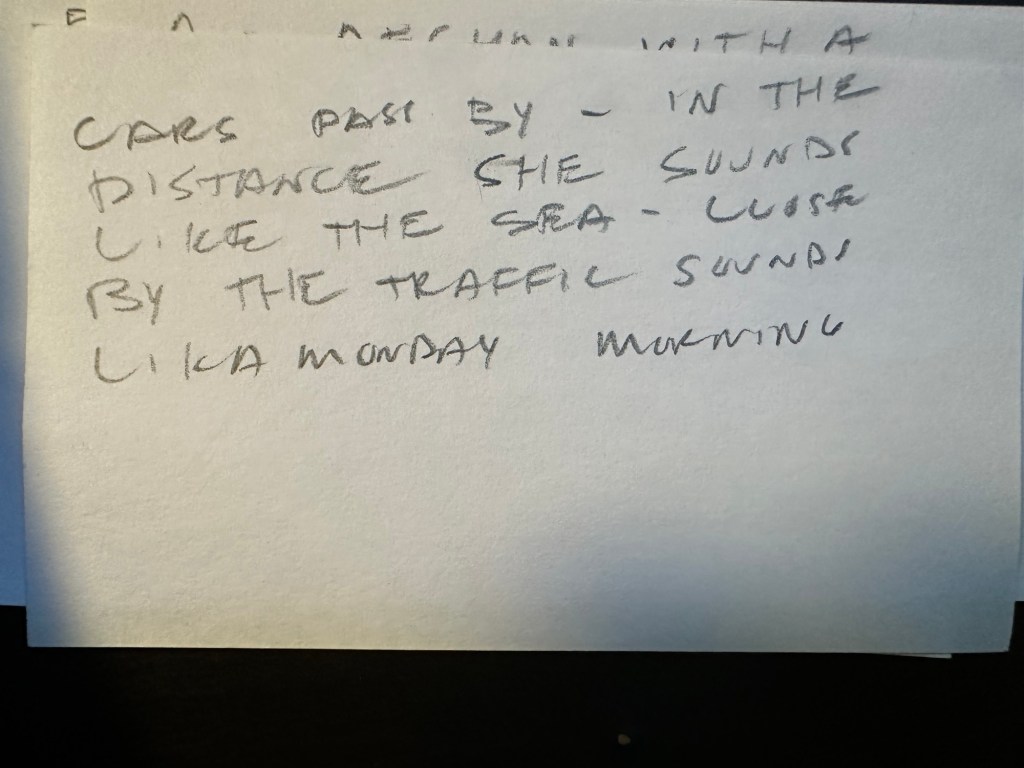

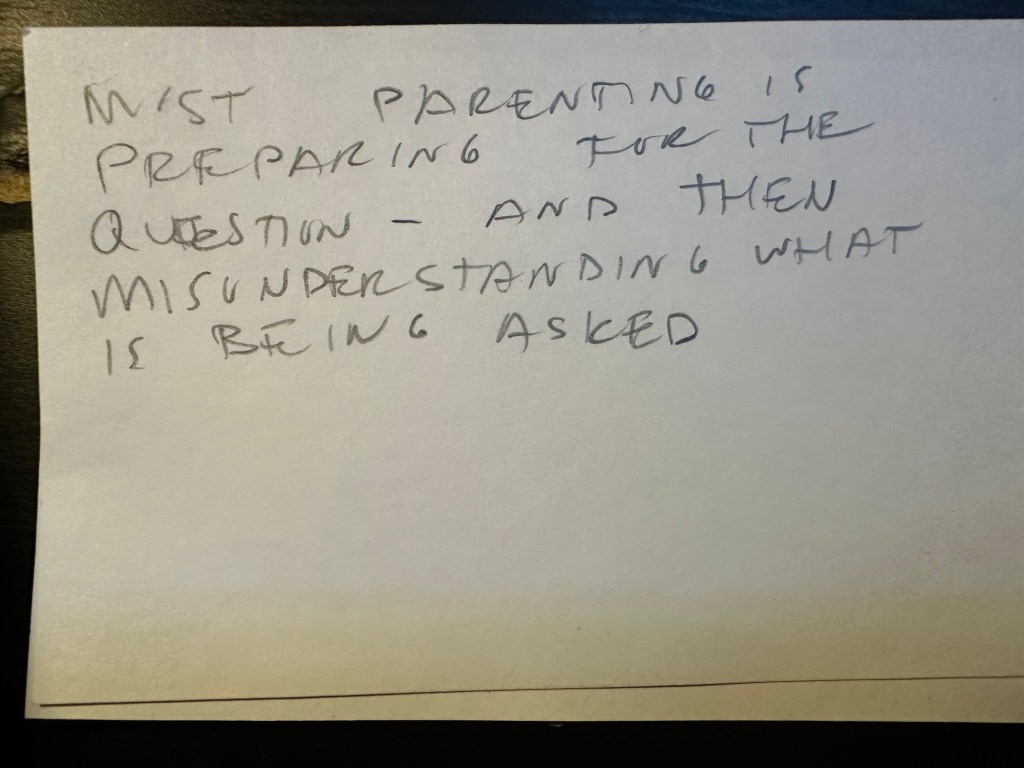

master class billy child session three

poem

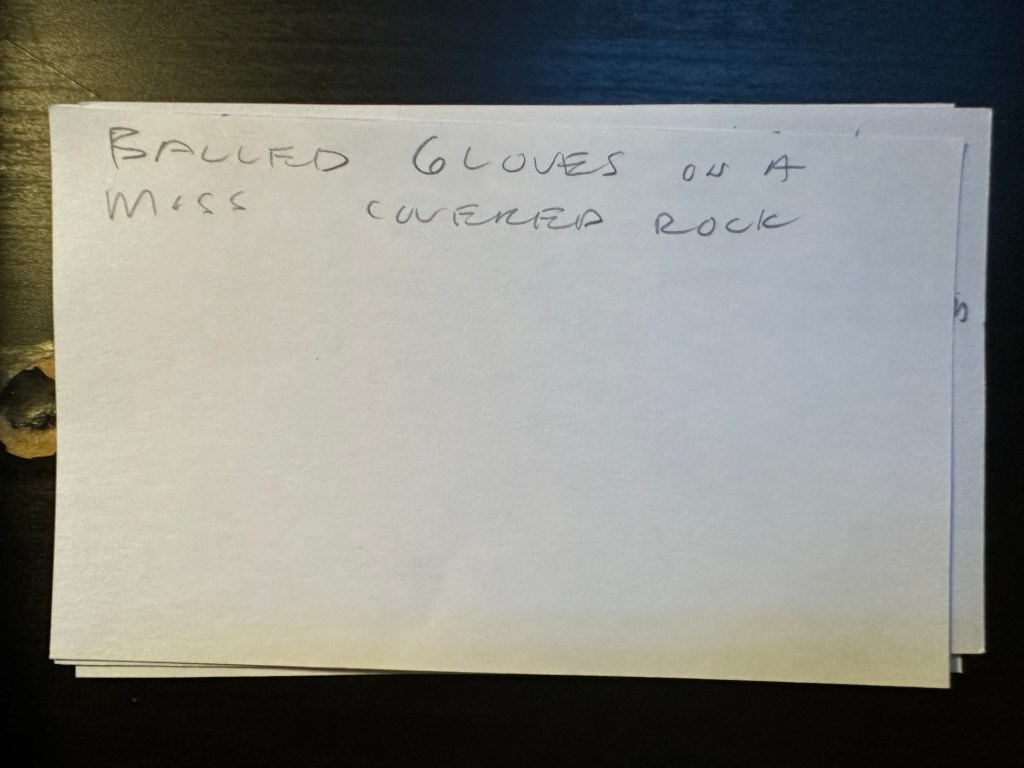

Balled glove on rock with yellow moss

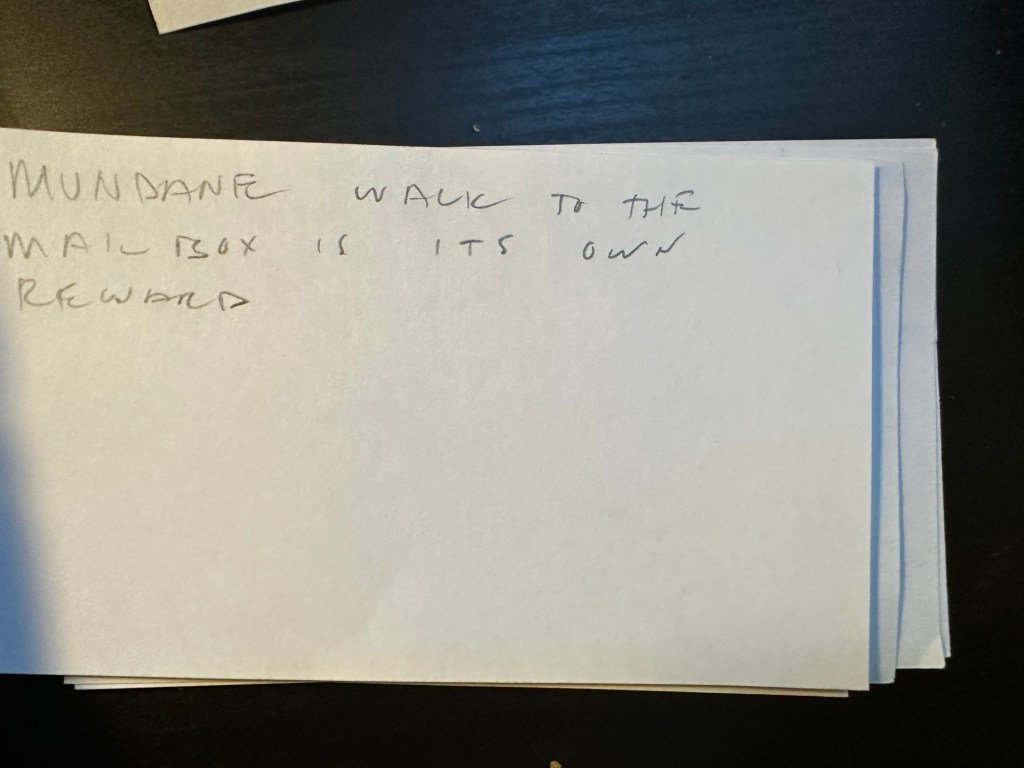

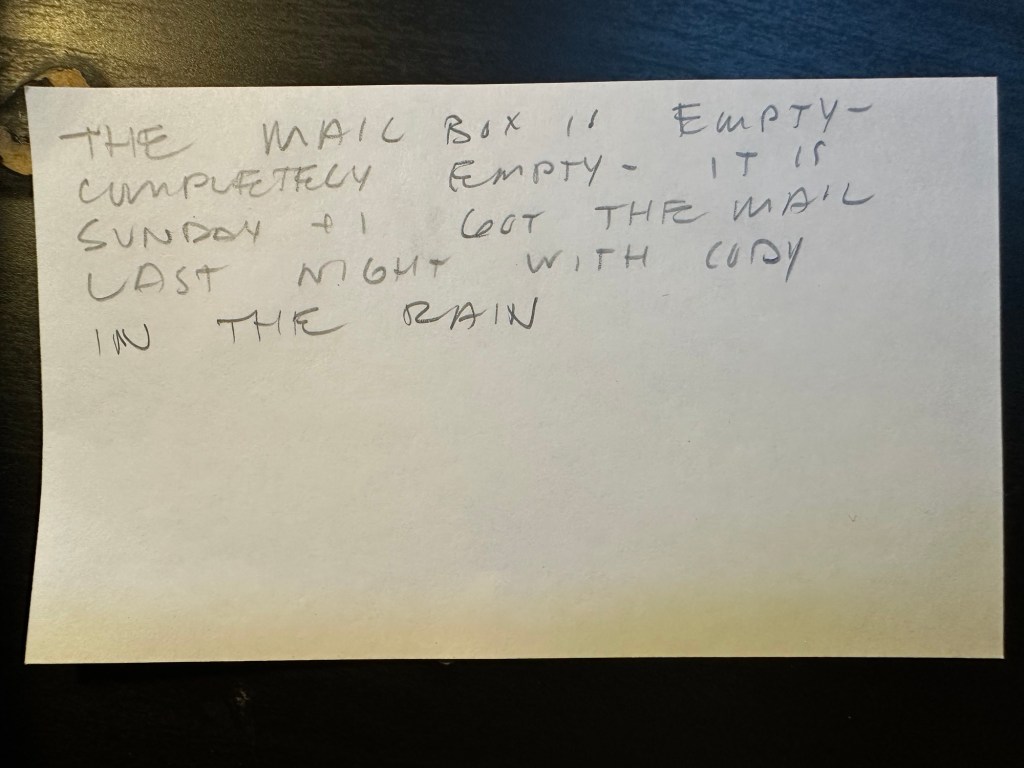

Mundane walk to the mailbox is its own reward.

The gloves are blue the moss is yellow.

Suburban winter evaporation in the shadows

Before the mailbox opens, I decide to buy a yellow scarf to match the red socks of summer I do not own.

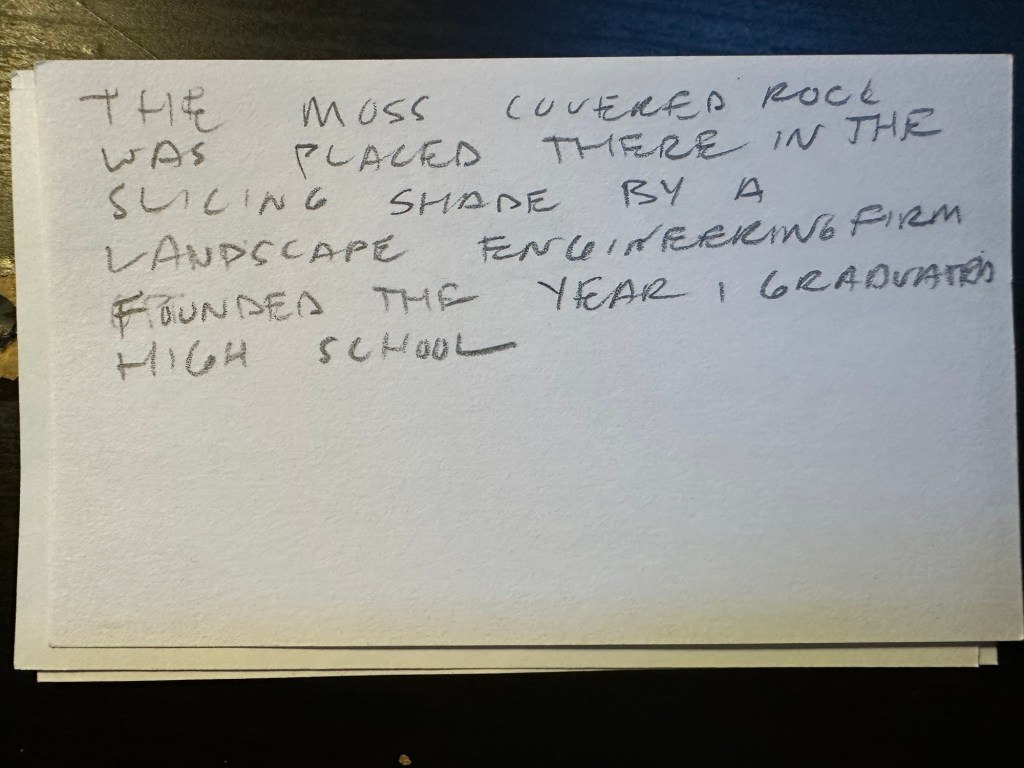

Balled gloves on a moss covered rock.

The mossy rock was placed there in the slicing shade by a landscape engineering firm founded the year I graduated high school.

chapter 03

billy collins

DISCOVERING THE SUBJECT

“There’s no chronology involved in poetry. You can go anywhere. You can be anywhere. You can fly.”Writing exercise

Every literary age comes with its own understanding of what is the appropriate subject matter for poetry. In the Elizabethan period, the dominant subject was romantic or courtly love. In the age of the English Romantic poets, you were supposed to write about nature. Poetry advances when these rules of accept-ability are violated. Think about Walt Whitman: when he should have been writing about nature, he wrote about machinery. Thom Gunn wrote a poem about Elvis Presley when pop stars were not considered appropriate for poetry. Both poets violated the literary decorum of their time. In choosing what to write about, nothing is too trivial. Don’t censor yourself. Don’t feel that you have to be serious, or even sincere. You can be playful, even sarcastic in your poems. Think of a subject that may seem outside of today’s literary decorum and write a poem about it.

Writing exercise

Choose an object close by—whether you’re in an office or a kitchen, a park or a library—and describe it. Start with a description of this object and see what it opens up for you. Does it evoke personal memories, have cultural implications, or elicit an emotion? Write a

poem that starts with this object, then leads the reader into the more personal memory.Writing exercise

Make my hand-of-cards analogy concrete. Think of a topic. Take ten blank flash cards and on one side of each flash card, write a line about this topic. Use a mixture of emotional detail, concrete detail, and images when writing these lines. Now, put all these cards face down in front of you. Now turn five of these cards over, face-up. What kind of poem is this? What questions remain? Experiment with which five cards should be turned up in order to create a poem that is both mysterious and clear enough for the emotions to be anchored.

WORKING WITH FORM

“What you have to do in

your poetry is tell a little

white lie. Harmless, but it’s

a lie. And the lie is that you

love poetry more than you

love yourself.”Writing Exercise

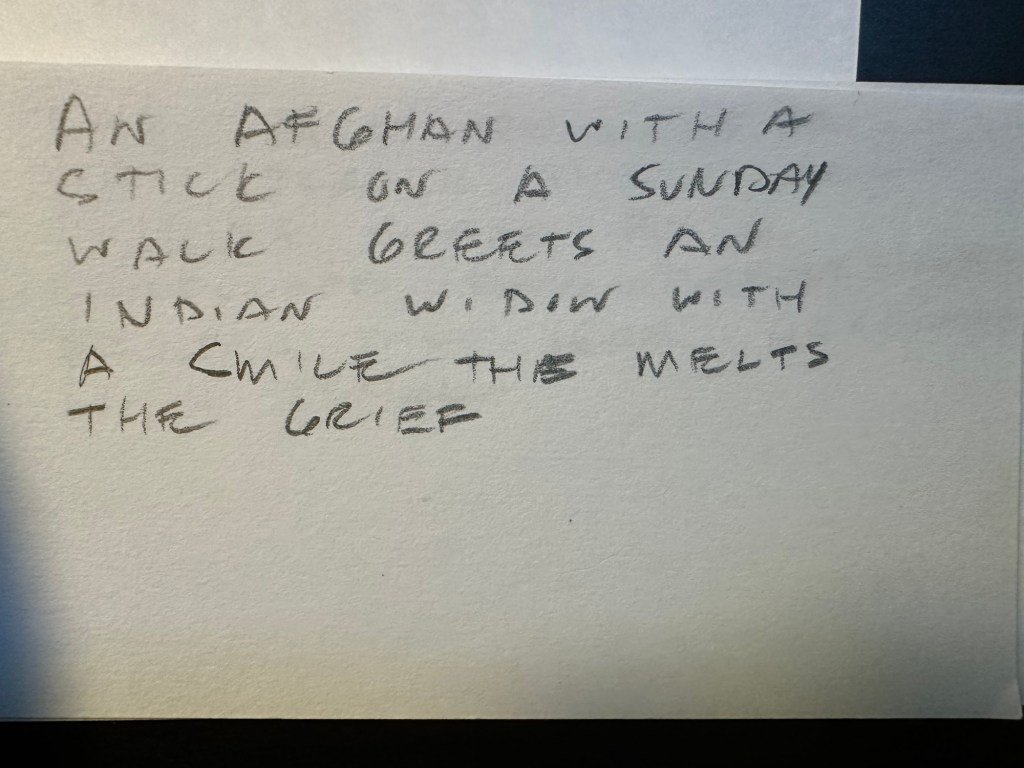

Go on a walk and bring your notebook. Look around

and take down some observations on the external

stimuli around you—a tree, a person, a neighborhood,

a pool. See if you can begin a poem by using some of

these external elements. Once you’ve got the poem

underway, have you made a decision about what your

stanzas will look like? Will you use enjambment or will

you use punctuation? Do you want the poem to go

slowly or faster? Do you want to use long sentences or

short?Reading Exercise

There are two major things poets can learn from the

short stories of Anton Chekhov. One is the use of

very specific detail—the particulars of experience—to

keep the story anchored to external reality. So too can

poets use detail to anchor a poem. The other is the

use of inconclusive or “soft” endings. Chekhov does

not solve problems for the characters. Similarly, the

endings of poems do not need to resolve things. A soft

ending—when a poem just ends in an image—can work.

Read a short story or two by Anton Chekhov,

keeping an eye for those literary techniques that you

can apply to your poems. “Misery” and “The Lady with

the Lap Dog” are highly recommended.Writing Exercise

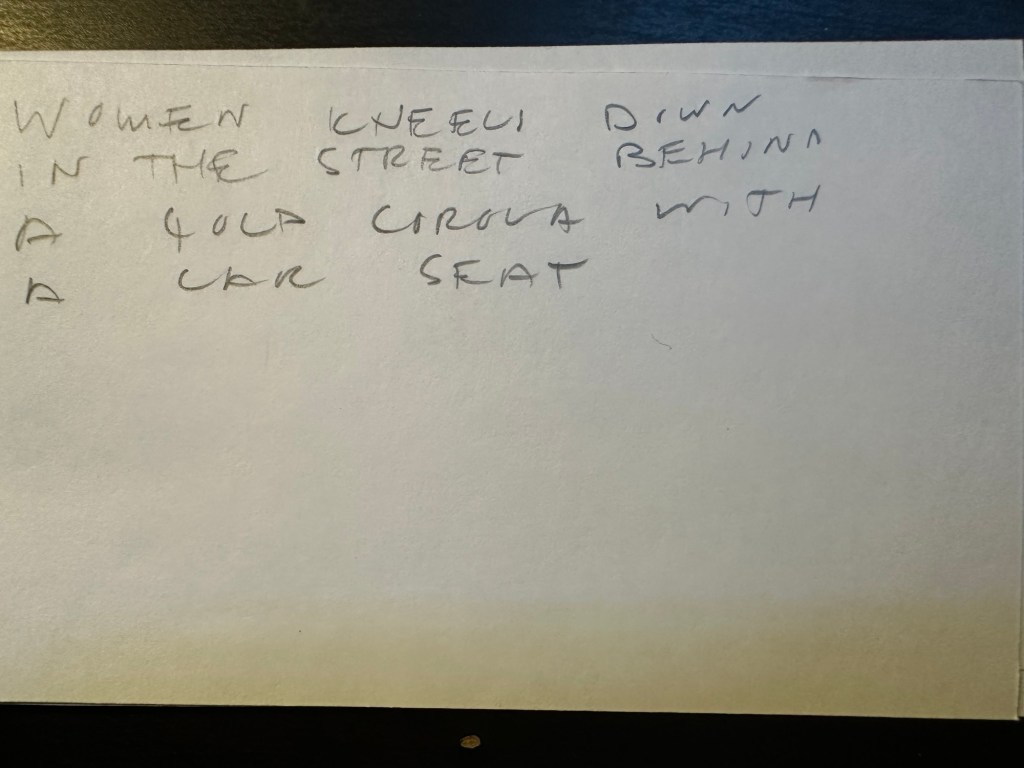

Write a few lines setting a scene that is easy to accept.

Think about the example of snow on pine trees or a

dog lying under a hammock. Establish a scene of your

own. Then have your poem take a twist. Take your

reader and yourself somewhere very different—spatially

or thematically—from your original scene.Writing Exercise

Think about the stanzas as various “rooms” in the

house of the poem. Imagine that the poet is taking

readers through various rooms in a tour of a house.

Now, read one of your own poems and look at the

stanzas: in the margins of your poem, write down what

each stanza or “room” is revealing.